Happy New Year y’all!

If you overindulged in last night’s new year’s celebrations and are currently paying the price, you might want to leave this post for another day – it contains lots of words and numbers and bright colours; perhaps more than your pickled brain can take in at the moment. Go nurse your hangover and come back later. For those of you who were better behaved last night, read on….

In my last post I presented an overview of Munsell’s Colour Classification System – I know it seems an overly complex approach to colour, especially as it relates to garden design, but understanding the concepts of Hue, Value and Chroma is key to effective use of colour in the garden.

Munsell’s three-attribute system is the basis for numerous colour models; for example, the Royal Horticultural Society uses a similar numeric system, employing the terms Hue, Brightness (Munsell’s Value) and Saturation (Munsell’s Chroma). Other models use such terms as Hue/Luminance/Saturation, Hue/Lightness/Saturation or Hue/Value/Saturation. In this post and in general, I use the latter; Hue, Value and Saturation – but in a Munsell framework. A purist might say I’m mixing modalities, arguing that chroma and saturation are not quite the same, but for our purposes they are close enough (I am simplifying things considerably). Today then, I’ll take a closer look at Hue.

Technically speaking, Hue refers to position on the spectrum. That ‘regular Joe’ I spoke of in my last post, was actually defining the attribute of hue – it is the response of colour receptors in our eyes (cones) to light absorbed by and reflected back from an object. The frequency and wavelength of that light determines its colour, red being the longest wavelength and violet the shortest.

Visible spectrum of light – violet light has the shortest wavelength and red the longest.

Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Hue is also the attribute that provides the emotional impact – red is passionate; the colour of anger or cupid’s arrow, yellow is happy and optimistic. It should be noted here that the human response to a particular hue isn’t universal – it’s determined largely by our culture, and by personal experience. The colour red in China symbolizes good luck and prosperity, in India it means purity, and in Hebrew tradition it represents sacrifice and sin. Blue may feel cool and calm to most, but if an individual experienced something traumatic in a room painted blue, that colour may forever trigger negative emotions. Case in point; many people experience bright yellow as a cheerful colour – I find it nauseating. When I was in my mid twenties I took up knitting (for whatever reason knitting had become a fad among young women at the time). I’d been working on a bright yellow mohair sweater (what can I say, it was the eighties and we all wore big hair, big shoulders and big colour). I stayed up late one night trying to finish this furry fright, and after hours of focusing on the gaudy garment, I went to sleep still visualizing bright yellow – indeed the colour permeated my dreams. I awoke several hours later feeling quite nauseous (apparently I’d come down with a nasty gastrointestinal bug). As I drifted in and out of near-delirious, nausea-interrupted sleep, I was still dreaming yellow. Once an association is made between a visual stimuli (or any stimuli) and an emotional or physical response, it may be with us for a lifetime. To this day bright yellow can still make me queasy.

The colour red has great significance in Japanese culture, symbolizing among other things, that which is sacred – hence the red bridge or ‘Guzei’ in the Japanese Garden represents the path to salvation or redemption. Photo: Pat Gaviller

Primary Hues

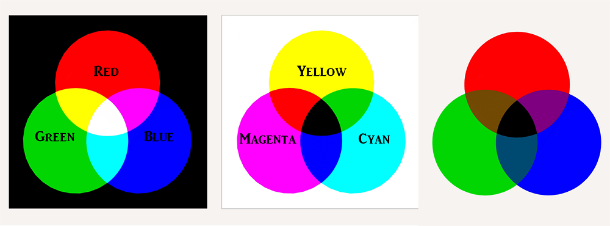

Perhaps you’ve heard conflicting information as to which hues are the primaries – are they red, green and blue? Cyan, magenta and yellow? Red, yellow and blue? The correct answer is… all of them – it just depends which model you’re considering. The additive colour system, or RGB (red, green, blue) model, refers to the combining of red, green and blue light to produce a broad range of perceived colours – your computer monitor, television screen, and that awesome light show accompanying your favourite rock band in concert, utilize this model. The subtractive model, or CMYK is used in ink colorant systems, your inkjet printer for example – cyan, magenta and yellow are the primaries in this model.

The RYB (red, yellow, blue) model was the original subtractive model, predating colour science – it was replaced by CMYK since it is believed that more colours can be produced using the primaries of cyan, magenta and yellow than with red, yellow and blue. Nonetheless, RYB is still used by artists, especially painters. It is also an effective illustrative model which I too utilize and will discuss later in this post.

So what does all this have to with us? As gardeners, we manipulate neither light for digital media application, nor pigment for printing or painting. However, we do manipulate plants, the colour of which comes from pigments, and the light that shines on them – an understanding of the applicable colour models is therefore beneficial.

To complicate things further, the human eye blends colours differently again, in a phenomenon called optical mixing. Ever have the experience of trying to match a print fabric skirt or shirt with a solid colour blouse or tie? You may have perfectly matched one of the colours in the print, but when you view the pairing from a few feet away, the colours appear to clash. The eye has blended together the various colours in the print to make an entirely different colour – this optical mixing is especially evident with small patterns, less so with larger blocks of colour. As we continue our exploration of colour properties, you will see that this comes into play often in the garden.

Left: Additive mixing – primaries are Red, Green and Blue. Middle: Subtractive mixing – primaries are Cyan, Magenta and Yellow. Note that the secondary colours of one system are the primaries of the other. Right: Optical Mixing – Colour mixing according to the human eye. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Munsell’s aim was to develop an approach to colour that approximated the way the eye perceives it. Like his predecessors, beginning with Isaac Newton, he conceptualized the visible spectrum of light as a circle of hues. This was of much more use to artists and designers than the linear spectrum – by placing red next to violet it allowed for red-violet combinations and also provided a better tool for visualizing colour relationships, e.g. opposites or complements.

The Basic Hues

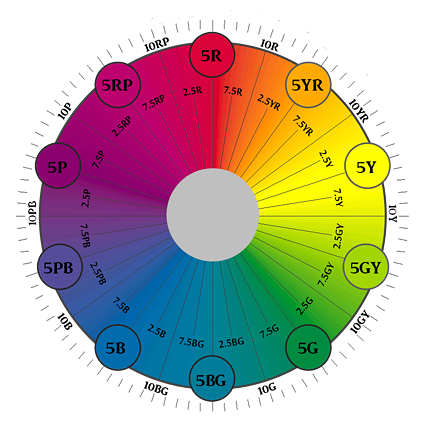

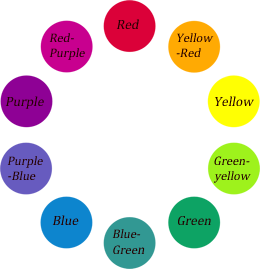

Munsell organized hues into a circle of five major hues (Red, Yellow, Green, Blue and Purple) and five minor hues (Yellow-Red, Green-Yellow, Blue-Green, Purple-Blue and Red-Purple). Together these comprise the Basic Hues and these basic hues are the colours which are most pure or saturated.

Graphics and Photos: Sue Gaviller

Intermediate Hues

The transition from one hue to another is a gradual one with many hues in between, so the spaces between the basic hues he divided further, allowing for intermediate hues. All the basic hues begin with 5, 5R being the basic hue of red, 5YR is yellow-red, 5Y is yellow etc. The intermediate hues all begin with 10 – 10R, 10YR, 10Y and so on around the circle.

Munsell’s Basic and Intermediate hues. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Consider the hues between 10RP and 10R; all are designated R – 2.5R is nearer to Red-Purple so will contain more of that hue, 5R is basic or pure red, 7.5R and 10R will contain increasing amounts of Yellow-Red (orange).

Numbers then begin at 2.5 again – 2.5YR has more red in it, 5YR is the basic hue of Yellow-Red and the hues 7.5YR and 10YR become increasingly more Yellow.

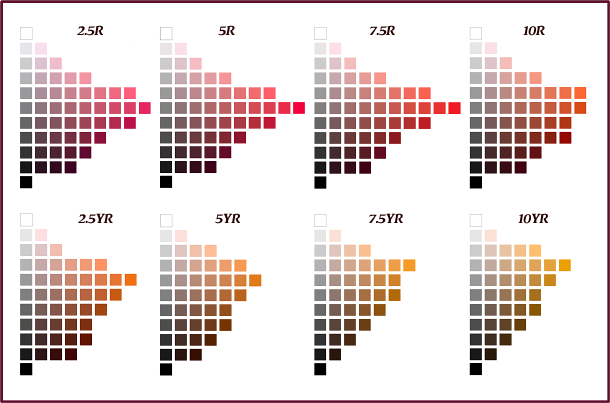

Each of these 40 numerically designated hues, has a corresponding page in the Munsell Book of Color. Each hue is a ‘family’ of colours with numerous value and chroma variations making up the page – below are some examples. Note that as the hues progress from one to another, the changes are subtle but still evident.

Eight different hue pages as they might appear in the Munsell book of colour. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

The Artist’s Wheel

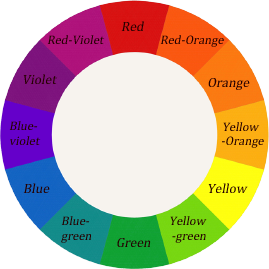

Okay enough of all this technical stuff – let’s look at the more familiar Standard Artist’s Wheel, the RYB model we all learned in grade school. It differs from Munsell’s hue circle in a number of ways; instead of five major hues and five minor hues, there are three primary colours (Red, Yellow and Blue), three secondary colours (orange, green and violet), and six tertiary colours (red-orange, yellow-orange, yellow-green, blue-green, blue-violet, and red-violet).

Artist’s Wheel. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Munsell Hue Circle. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

As well, some of the colours are named differently; violet instead of purple, orange instead of yellow-red, yellow-green instead of green-yellow etc.. More significantly, Munsell’s circle contains ten basic hues whereas the Artist’s wheel has 12. This means that the complementary pairs will differ as well – red & green vs. red & blue-green, red-violet & yellow-green vs. red-purple & green. The only exception is blue and orange (Munsell’s Yellow-Red) which are the same on both wheels. Munsell used the term opposite rather than complementary and he believed that in order for two colours to be truly opposite, they had to completely neutralize each other when mixed together, hence producing grey. This was how he arrived at the ten basic hues.

So which of these circular representations of hues is most useful to us? Well either… or both – some would argue that Munsell’s opposites are less jarring when used together than the traditional complements. The Artists wheel, on the other hand, works out colour schemes better because 12 colours can be divided more ways than 10. I use both, but always with Munsell’s basic premises in mind.

Contrasting Hues

Pairing hues that are distant from each other on the colour wheel (e.g. opposites or complements) creates high contrast. These dynamic colour combinations really draw the eye, thus overuse can cause visual fatigue or appear garish.

This vignette from an area in my front garden demonstrates the highly contrasting hue combination of red-violet and yellow-green. A lovely combo, but too much of such intense contrast could easily overwhelm a composition. Photo: Pat Gaviller

Hues that are close to or beside each other on the colour wheel result in low contrast when used together. This causes less visual tension and is therefore more restful.

Blues and purples are near to each other on the colour wheel resulting in a low contrast composition that is visually softer than high contrast scenarios. Photo: Jane Reksten

Of course too little contrast can also end up creating monotony, so be sure to use some areas of high contrast and some areas of lower contrast. I also recommend that you limit the number of hues in your design. This is less constricting than you may think – remember each hue has a whole family of colours associated with it, with varying value and saturation levels, meaning many different but related colours.

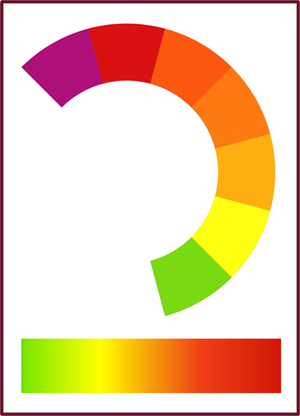

Warm Hues

Warm hues. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Hues are described as either warm or cool – warm hues are those on the right side of the spectrum and cool hues are those on the left. Red-violet, though it doesn’t exist on the spectrum, can be considered warm or cool because it has both red and violet in it.

Warm hues are lively and vibrant and create the optical illusion of advancing toward the viewer, which means they appear closer than they actually are. For these reasons they are real attention-grabbers, especially at full saturation – gardeners make the mistake of overusing these eye-catching hues thereby overpowering all other aspects of the garden. Warm is dominant and little is needed to make a powerful statement.

Kendall Jackson winery, Sonoma County CA. Splashes of warm reds and yellows are all that’s needed to provide sufficient visual punch without overshadowing other important elements of the design: line, form and texture. Photo: Sue Gaviller.

Cool Hues

Cool hues. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Cool hues are subtle and restrained, therefore won’t overwhelm a garden design. Optically they recede from the observer, appearing further away – best to situate them up close where they are most visible.

As I mentioned earlier, there may be personal and cultural associations that come into play regarding our emotional response to various colours, but there is in fact a physiological reason for our ocular response. The eye focuses on distant objects in much the same way it focuses on green or blue, and on near objects much the same way as on red. Since the eye is more at rest when viewing objects in the distance, it perceives cool blues and greens as more restful.

A peaceful composition of cool greens, blue-green, blue, and soft violet in an Oregon shade garden. Photo: Sue Gaviller

When contrasting warm and cool hues, cool should outweigh warm by at least three to one. If you follow the rule of thumb that green should be the predominant hue in your garden, this ratio will be easy to satisfy. Unfortunately, in our attempt to create season long colour, we include too many brightly coloured foliage plants, sometimes to the near-exclusion of green. Fellow gardeners please remember, green is good. Green is to the gardener as a canvas to the artist – it is the backdrop against which all other hues are set.

The image on the left contains too many warm colours without enough green. The image on the right has been been photoshopped to illustrate the balancing effect of green. Photo: Sue Gaviller

Well my friends you are one step closer to painting your garden masterpiece, but there’s still more to learn – next post I’ll explore the colour attribute of Value.

’Til then, Sue

Happy New Year Sue and thanks for all of the fantastic blogs over the past year. I hope they continue. I won’t be reading this today and not because I overindulged yesterday but that I had the flu all Christmas and still getting over it. All the very best in the New Year

Shirley

Happy New Year Shirley – nice to hear from you! Sorry to hear you’ve been sick though. Hope you feel better soon – and enjoy the blog post when you get around to reading it. I’m sure it will just be a refresher for you.

Take care and thanks for reading,

Sue

Its quite possible you have the best gardening blog in the industry.

Well that’s mighty high praise Jimmy Dean – thank you very much – and thanks for reading.

Sue

I think this is the most thorough post I have ever read on hue and color. I like your graphic with the flowers too. You illustrated with some beautiful garden images too. I also agree with you in garden design, many have too many colors in the garden without having a place for the eye to rest along the way. I think that is what separates it from landscape design where “green” is very important as is having color and texture extend the visual interest year round.

Hi Donna,

Thanks for your kind comments – glad you enjoyed this second post in my colour theory series. I have barely scratched the surface of course, so stay tuned; I’ll be posting the next in the series in a few days.

Thanks for reading,

Sue