Top o’ the mornin’ to all ye lads and lasses. Today is St. Patrick’s Day – a good day to celebrate all things green don’t ya think? Not so green ’round here though is it?

Well soon enough my friends, soon enough. Spring will come – in the meantime we still have a ways to go in our study of plant form, texture and colour. I’ll try to have you ready in time for the frenetic plant-shopping sprees that will begin in the next month or so.

Continuing our exploration of plant form then…. next up are grafted standards and topiary forms.

Grafted Standards

A grafted standard is essentially a shrub grafted onto a stem or “standard” – also called a top-graft, the overall effect is that of a stick with a ball on top. If that sounds disparaging, it isn’t intended to – they’re actually very attractive additions to the landscape. Many different shrubs can be grafted this way, but the ones that work best are those that are smallish with a naturally round(ish) growth habit – this means minimal pruning will be required. Dwarf Korean lilac, globe spruce and globe Caragana are all commonly used and available in grafted form at most nurseries.

Depending on the particular shrub used, the height of the standard, and how it is pruned, this form can have several landscape or garden applications. They work well as linear plantings to emphasize a design line – both curving and straight design lines can be planted this way.

I designed this fence/wall combo to prevent weed encroachment from a neighbouring property onto my client’s property. It nicely showcases these three top-graft globe spruce. Photo: Sue Gaviller

A row of grafted Syringa meyeri standards accentuates a curving fence line. Photo: Sue Gaviller

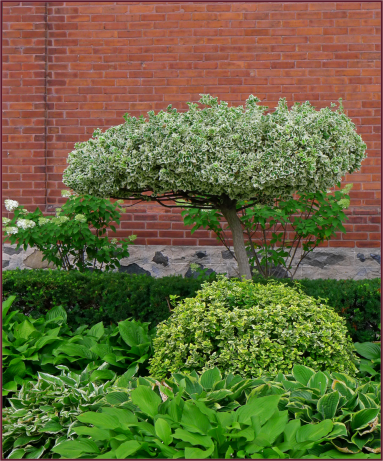

This oddly shaped Euonymus fortunei standard makes a unique feature tree. Photo: Pat Gaviller

If they’re tallish and not too wide, two top-grafted standards on either side of an entryway, can make an attractive frame – not so much, if they’re short and stout though; these are best used as single specimens.

I find this form to be especially useful when designing certain theme gardens, most notably Mediterranean, Colonial and English Landscape Style.

Left – Top-graft Syringa meyeri is underplanted with Lavandula angustifolia ‘Hidcote’ in a client’s Mediterranean-inspired back yard. Photo: Pat Gaviller

Right – Two potted standards gracefully frame an arched entryway for a Tuscan wedding reception. Photo: Cathy Gaviller

As a general rule grafted standards don’t work in groups (unless planted in a row along a design line), but there are of course exceptions to every rule – see below.

Planting standards in a triad isn’t usually recommended, but in this scenario they are all different heights and widths – the end result is therefore quite pleasing. I suspect this was purposeful – very clever in fact.

Photo: Pat Gaviller

Topiary

Topiary is the practice of shearing woody plant material into… well, just about any shape you can imagine. My intention here isn’t to instruct you in the art of plant sculpture (my attempt at topiary would likely result in something akin to Richard Dreyfuss’s infamous mashed potato mountain), but rather to instruct you in their appropriate use. Of course a shrub can be sculpted into a mouse, a monkey, or a monster but the most common forms you’ll find at a nursery are standards, pom–poms, poodle tiers and spirals.

Standards

These are created by pruning a large shrub, which is naturally multi-stemmed, into a single-stem, tree-like form with a ball-shaped top. They look pretty much the same as a grafted standard – in fact now that I think of it, a couple of the photos in this post were of standards I just assumed were grafted, but they could well have been shrubs that had been pruned to a single trunk, rather than grafted. No matter, their application is exactly the same.

Pom-poms

Pom-pom topiary is formed from a shrub that is pruned into several main stems with a “ball” of foliage at the end of each. This is a very unique form and should be used as a lone specimen – this means only one in your entire composition. No grouping, repeating, planting in a row, or framing – they’re the wrong shape for any of these applications.

Pom-pom topiary has such distinctive form that it must stand alone, like this lovely pine, which has been situated beautifully. Photo: Pat Gaviller

This landscape is one I’ve featured before – I love its clean lines and minimalistic style. While I don’t as a rule choose to critique another’s work on this blog, for the sake of a teaching moment, I will suggest that the pom-pom pine might have greater effect without the Syringa meyeri standards to compete with.

Photo: Sue Gaviller

Pom-poms, especially pines, can lend an Asian feel to a garden composition because they, like bonsai, are part of the Japanese aesthetic. Topiary and bonsai are used to create Reduced Scale, an important Japanese design principle which refers to the reproduction in miniature, of scenes in nature – bonsai and topiary are used to fashion “trees”, but in much-reduced scale. For this reason, it is acceptable to use more than one of these forms in a Japanese garden composition.

A modified form of pom-pom topiary, cloud pruning is used to create the impression of aged and weathered trees. Photo: Pat Gaviller, Butchart Gardens Victoria, B.C.

Poodle Tiers

A potted two-tier poodle topiary makes a pretty statement. Photo: Deborah Silver, Dirt Simple

This form is a single trunk with two or more individual balls of foliage along its length. Poodle tiers are fairly upright specimens, which makes them an appropriate choice for framing views and entryways. They also make excellent single features. Like topiary standards and grafted standards, poodle tiers are especially suited to Mediterranean style gardens, formal Colonial style gardens and English Landscape gardens.

Left: This Spanish Mediterranean-style home is suitably landscaped, except for the two pom-pom topiaries. While the goal may have been to frame the entrance, their form doesn’t effectively serve this purpose.

Photo: Patti Cartier

Right: A graphic depiction of the more appropriate 3-tiered poodle topiary providing the desired frame.

Spirals

Spiral topiary is an upright form that has been pruned into a spiral or corkscrew shape. These forms have the same application as poodle tiers and standards – they’re elegant as single specimens, or repeated sequentially along a design line, are suitable for framing, and are fine additions to theme gardens like Colonial, Mediterranean or English Landscape.

Two spiral junipers frame the entrance to a lavish outdoor ‘sitting room’.

Photo: Deborah Silver, Dirt Simple

In our climate most garden topiary is Juniperus chinensis, Juniperus scopulorum or Juniperus virginiana, as well as several Pinus species. In warmer climes, Boxwood, Yew, False Cypress, Rosemary and Bay Laurel are used. These are often available as potted annuals for us Northern gardeners, and given a sunny window, they might overwinter indoors.

Topiary and grafted standards present very strong form in the landscape – suitably sited, they will bring style and sophistication to your garden.

Happy St. Pat’s Day – just think green. SueRelated articles

- The Form of Things to Come (notanothergardeningblog.com)

- The Form of Things to Come, Part 3 – Weeping Form (notanothergardeningblog.com)

- The Form of Things to Come – Part 2 (notanothergardeningblog.com)