I promised myself I wouldn’t begin today’s post with comments or complaints about our wintry weather as I did in three of my last four posts. I don’t want readers to get the erroneous impression that Canada is the land of perpetual ice and snow. Nor do I want readers to think all Calgarians are a bunch of weather-whiners. And I certainly don’t want you to think that whining about the weather is my shtick – the hippy dippy weather girl, or that it’s the only intro I can come up with. Because it’s not. I have plenty of clever intros up my sleeve – clever is my middle name. So how about this… nah, okay then how about…. dagnabbit, folks that’s all I got today. I just wanna whine about the weather okay?

Correct me if I’m wrong fellow Calgarians, but has it not been an extraordinarily long winter? I know it’s only the middle of April but Spring isn’t even trying anymore. She just teased us and left us high and dry – well more like cold and wet. Even my stoic husband, who chides weather-whiners for bemoaning that which they can’t control, has on two recent occasions grumbled about the weather. “This weather is sucking the life out of me,” he lamented last night.

Today I look out my window at snow-covered branches, knowing there’s more snow in the forecast – I don’t even think it makes for a pretty picture anymore. I feel like I’m in Narnia under the white witch’s rule – where “it’s always winter, but never Christmas” (uttered with the most refined of British accents). Enough already old man winter – go away.

Okay I’m done complaining now. I’m not even going to attempt a smart segue into today’s topic, I’m just going to start right in on rounds and mounds and flats and mats. If you’re joining me for the first time, you may wonder what on earth I’m talking about – if you’ve been following my latest series of posts, you’ll know of course that I’m referring to plant form.

Round/Mound

Rounded plant forms grow in a roughly spherical shape. Mounds are somewhat flattened rounds. These “roundy-moundys”, as my design instructor called them, are the most common form. They are non-directional, meaning they don’t send the eye up or down – rather the eye just glides over them and moves through the landscape in an undulating kind of progression.

This rolling English landscape consists mostly of rounded/mounding trees and shrubs. Photo: Marny Estep

Rounds and mounds are relatively neutral and soft, thus aren’t particularly dominant forms. They can be massed, work well grouped in threes, and a single round form, if large, can make an effective anchor. As well these forms can “echo” other curvy forms.

A trio of globe-shaped Cherry Bomb barberry visually supports the more dominant weeping form of Walker’s caragana in a client’s garden. They also nicely echo the orbicular shape of the wall-mounted light fixture. Photo: Sue Gaviller

A large globe cedar provides a visual corner anchor. Photo: Sue Gaviller

Round forms are excellent foils for columnar forms like this Pinus sylvestris ‘Fastigiata’, but the effect would have more credibility if the heavily pruned globe-shaped evergreen had more natural form. Photo: Sue Gaviller

Despite the ubiquity of the round/mound form, gardeners and landscapers seem to want more of it, often pruning shrubs unnaturally into this shape. It may be that the form’s common presence leads to the mistaken notion that all shrubs are round; hence they all get pruned that way. Or it may be that gardeners intuit the gentle movement that results from the use of rounded or mounding forms in the landscape.

Regardless, this pruning style can sometimes produce attractive results and sometimes not.

Cornus sericea has a naturally round form. Photo: Sue Gaviller

While Cotoneaster lucidus grows naturally as a very large loosely shaped ball, this homeowner has pruned them into an attractive rhythmic sequence of perfect spheres. Photo: Pat Gaviller

Geometric forms like these roundly sheared boxwood, abound in formal landscapes. Note the very rolling movement that results, especially when planted sequentially. Photo: Jane Reksten

This form is common in certain theme gardens – for example, in the Japanese garden, shrubs are pruned into globose forms to mimic rocks, an important component in their garden compositions.

Formal gardens too, utilize very round shapes as well as other strong geometric forms.

In this formal landscape, shrubs have been pruned to repeat the shape of the stone spheres .

Photo: Marny Estep.

Three mounded shrubs pruned to symbolize rocks. Japanese Garden, UBC. Photo: Ann Van de Reep

Keep in mind that despite their relative neutrality, round forms can be overused – so use them freely but make sure you punctuate periodically with other forms.

Flat/Mat

Flat forms are much wider than they are tall, and of course flat. If they have any appreciable curve to their upper surface then they are actually mounds – due to the undulating movement the curved surface creates. Flat forms that hug the ground and create spreading groundcovers are mats.

Spreading Juniperus sabina ‘Calgary Carpet’ underplants Syringa reticulata ‘Golden Eclipse’ in a client’s front yard.

Photo: Sue Gaviller

Like rounded and mounding forms, flat and mat forms are very common.

They are the most neutral of all the plant forms, making them excellent backdrops or underplantings for other more significant elements, like a focal point or specimen tree.

Their shorter stature and flattened surface, relate the scale of the garden to the horizontal plane of the ground.

Various Juniperus sabina and horizontalis cultivars underplant other trees and shrubs and effectively delineate the planting space and the lawn. Photo: Sue Gaviller

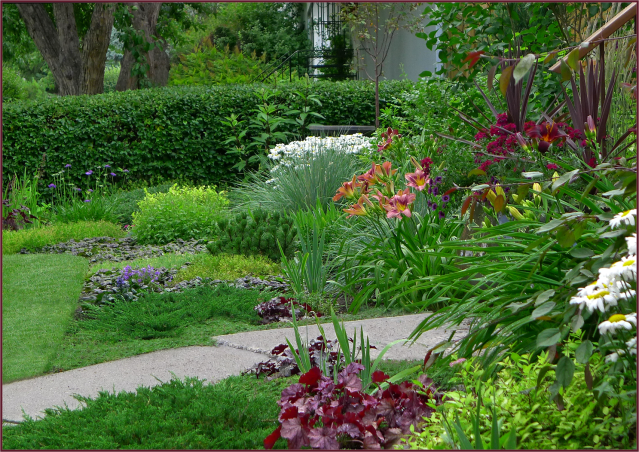

In addition, flat and mat forms transition the landscape from pathways or lawn into the garden, thereby connecting them.

Numerous flat and mat forms in my front garden provide a transition zone, connecting the lawn to the garden. Photo: Sue Gaviller

The mat form of Thymus pseudolanuginosis provides transition from sidewalk to garden and softens the straight lines of the pathways. Photo: Cathy Gaviller

Well my friends I’ve reached the end of my discussion on plant form. Texture and colour are next, but I think I’ll postpone those until our gardens wake up a bit and allow for some new ‘photo pursuits’. I’ll come up with some other topics to write about in the interim, so do stay tuned.

As I’m preparing to publish this post, I’ve become aware of the scary events that occurred in Boston earlier today – our weather woes seem suddenly pretty trivial. I won’t complain again anytime soon.

Be sure to hug your loved ones tonight.

Til next time, SueRelated articles

- The Form of Things to Come (notanothergardeningblog.com)

- The Form of Things to Come Part 2 (notanothergardeningblog.com)

- The Form of Things to Come Part 3 (notanothergardeningblog.com)

- The Form of Things to Come Part 4 (notanothergardeningblog.com)

- The Form of Things to Come – Part Five (notanothergardeningblog.com)

© Sue Gaviller and Not Another Gardening Blog 2012.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sue Gaviller and Not Another Gardening Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.