Over my last 8 posts I have looked at colour theory in considerable depth, focussing of course on its application in garden design. One of the most powerful ways we can utilize this knowledge is by experimenting with colour schemes in our gardens.

Many gardeners balk at the idea of purposefully employing a garden colour scheme, assuming it’s just one more rule to follow, or at the very least, too restrictive.

Utilizing a colour scheme doesn’t have to be restrictive though, if we think rather in terms of a hue scheme. Looking to the Munsell Book of Colour, we find that for each hue, there are many permutations of value and saturation all arranged on an individual page. So if we want to work with a scheme which includes red, we have a whole hue page to choose from – just for red! The other hues in our scheme afford us the same broad selection of colours. A little less restrictive than you thought, right?

Colour Schemes

A colour scheme is a planned or logical combination of hues on a colour wheel. As we discussed in earlier posts, there is more than one colour wheel, but you’ll probably find the artist’s colour wheel to be the most user-friendly. You can then refer to Munsell hue pages (or reasonable facsimile) for guidance with the various colours that fall within that hue. I do sometimes utilize Munsell’s hue circle to work out colour schemes, but they aren’t always as straightforward. For ease of use then, I am mixing models here.

So how does one go about choosing a colour scheme for the garden? If your house or other backdrop is a particularly strong chromatic colour, then it’s most effective if you include that colour in your scheme. If on the other hand, your house is more neutral, then start with a colour you really like and build from there.

The colours used in this restaurant patio planting echo the muted red and yellow hues of the siding on the building. Photo: Sue Gaviller

Keep in mind that most plants – both in your garden and in the surrounding landscape – have green foliage, hence green will always be present. Since this hue is so much a part of the outside world, the eye tends to ignore it, and will instead focus on other colours. Green is therefore experienced mostly as a backdrop for your garden composition. But it can certainly be one of the hues in your colour scheme too.

You can vary the colour schemes from one part of the garden to another (particularly if you have a large canvas), and the scheme can also change or evolve as the season progresses. For example a garden that has a yellow-green and red-violet combination in the spring might add other colours later in the season, but those hues must always be part of the scheme.

Realistically speaking, some scenarios don’t lend themselves to formal colour schemes (if only for the reason that the proprietor of a well established garden may not want to part with anything – just to incorporate a colour scheme). One can still play with colour schemes though; containers are a great way to experiment without committing to a particular composition.

So let’s have a look at what we can construct using the artist’s colour wheel and some Munsell hue pages.

Monochromatic colour schemes use various values and degrees of saturation of a single hue. Working with a single hue creates naturally harmonious colour compositions.

Monochromatic colour scheme using the hue of red-violet (5RP). Photo and graphics: Sue Gaviller

Complementary colour schemes contain two hues that are opposite each other on the colour wheel.

This is a high contrast colour combo, which means it can be loud and demand attention. So you’ll want to tame it by including numerous value/saturation variations of the pure hues – and of course lots of green.

Complementary Colour Scheme: Red-violet (5RP) and yellow-green (5GY). Photos: Top left – Pat Gaviller. Bottom and right – Sue Gaviller

Analogous colour schemes use two or three hues that are next to each other on the colour wheel.

Although this is a low contrast combination, analogous hues still benefit from utilizing variations in saturation and value of the chosen hues, thus introducing more variety. Remember if you choose warm hues, there will need to be significant green (foliage) in your composition to provide the necessary cool/warm balance.

Analogous Colour Scheme: red-orange (10R), orange (5YR) and yellow-orange (2.5Y). Photos and graphics: Sue Gaviller

Counterpoint schemes consist of a hue and one of the hues on either side of its complement.

This too is a dynamic colour combo, but somewhat less so than complementary compositions – many people prefer this colour duo as it generates less visual conflict. Again the use of variations in value and saturation of the two hues will create both unity and variety.

Counterpoint Colour Scheme: red (5R) and yellow-green (5GY). Photos and graphics: Sue Gaviller

Split-complementary schemes are three-hue combos that use one hue and the two hues on either side of its complement.

The split-complementary colour combo has all the dynamism of complementary and counterpoint, with the balancing addition of two hues that are closer together. A garden may transition from the aforementioned counterpoint theme to split-complementary as the growing season progresses and more plants (thus more colours) take the stage.

Split Complementary colour scheme: yellow (5Y), blue-violet (7.5PB) and red-violet (5RP). Photos: Top left – Cathy Gaviller. Right – Jane Reksten. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Analogous-complementary schemes use two adjacent hues and the complement of one of those hues.

Similar in effect to split-complementary, analogous-complementary schemes are especially soothing if the analogous constituents are cool hues.

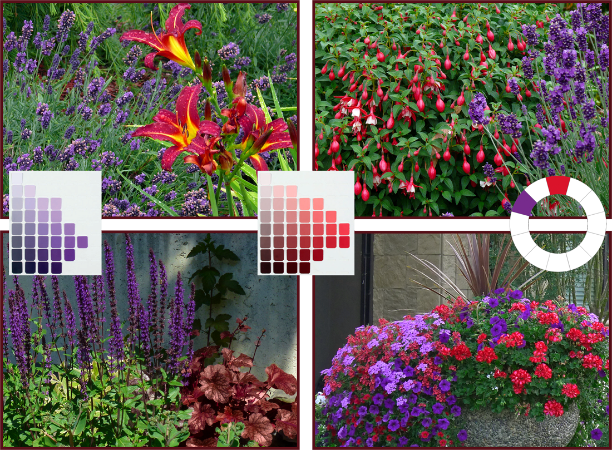

Analogous-complementary Colour Scheme: violet (5P), red-violet (5RP) and yellow-green (5GY). Photos: Top left – Pat Gaviller. Bottom left/right – Sue Gaviller. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Double-complementary schemes use two adjacent colors and the complements of both of those hues.

This four-hue scheme brings both drama (from opposites) and subtlety (from analogues) to a garden composition, and can be a natural seasonal transition from analogous-complementary as more plants come into bloom.

Double-complementary Colour Scheme: violet (5P), red-violet (5RP), yellow (5Y) and yellow-green (5GY). Photo and graphics: Sue Gaviller

Diads are colour schemes that consist of two hues located two spaces apart on the colour wheel.

Though this colour duo provides more contrast than an analogous scheme, it is still a low-contrast theme and less dramatic than higher contrast combinations. More contrast can be introduced if one of the hues is warm and one is cool, for example red and purple.

Diadic Colour Scheme: red (5R) and violet (5P). Photos: top – Pat Gaviller. Bottom – Sue Gaviller. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Triads use three hues that are equally spaced around the colour wheel.

Triadic schemes offer interesting colour combinations and are inherently balanced because the hues are all equidistant from each other.

Triadic Colour Scheme: blue-violet (7.5PB), orange-red (10R), and yellow-green (5GY). Photos and graphics: Sue Gaviller

Tetrads are colour schemes using four hues that are consistently spaced on the colour wheel.

- Square tetrad – 4 hues touched by the four corners of a square placed in the centre of the colour wheel.

- Rectangular tetrad – 4 hues touched by the four corners of a rectangle placed in the centre of the colour wheel

Four-hue schemes provide considerable colour choice thus can be quite vibrant, especially when hues are at full saturation. They can be toned down somewhat with the addition of less saturated versions of the pure hues.

Tetradic Colour Scheme: red-violet (5RP), orange (5R), yellow-green (5GY) and blue (5B). Photos and graphics: Sue Gaviller

You can see that with all the variations in value and saturation for each hue, many different but related colours are available to you – even when using only a couple of hues. Unfortunately, most of us don’t have access to the Munsell Book of Color, but there are numerous apps and online tools that will provide more than enough visual info for application in the garden.

I highly recommend the Virtual Munsell Color Wheel. It’s very easy to use – just bear in mind that it includes all the intermediate hues that lie between the basic hues (totaling 40 hues), which you may find overwhelming. The digital ‘hue pages’ aren’t identical to those in the Munsell Book of Colour either (copyright and such). You’ll also note that, compared to the traditional RYB colour wheel, Munsell’s blue (5B) appears more green and his purple-blue (5PB) more blue – this is because he divided the circular colour spectrum differently. I wouldn’t get too carried away with detail or accuracy though. Just choose your colour scheme using the artist’s colour wheel and find the hues that most closely approximate them on the Virtual Wheel.

Finding foliage or flowers in exactly the right colour may be next to impossible anyway. But don’t get discouraged. Remember green foliage abounds in the garden, and with all that ‘green between’, you’ll find that almost-the-right-colour will be close enough.

‘Til next time, Sue