They say sitting is the new smoking – which is to say, too much sitting is really bad for your health. Indeed recent research suggests it contributes to any number of illnesses. I’m pretty sure I don’t have any of these, but I can still attest to the perils of sitting too long. During gardening season, the long hours I spend sitting at my computer are offset by as many hours spent on my feet (or my knees) – digging and planting, pruning, deadheading, weeding and mulching. During the off season however, in addition to my design work I often write and/or lecture, so the many hours spent sitting at my computer become many more hours, especially when I have several deadlines to meet at once. It is then that my body rebels. I get sore and stiff – not from lifting and bending, squatting and kneeling – but from sitting.

As I write this I am nursing a back injury so painful I can hardly move. Did I hurt myself skiing or snowshoeing you ask? No I did not. Did I slip on the ice while out for a brisk walk? No I did not. Did it happen while vacuuming or moving furniture? No it did not. It happened while leaning over to put coffee grinds in the compost. In fact I suspect the very reason it happened is because I haven’t been lifting and bending, and squatting and kneeling. I have been sitting.

Ironic then, that the subject of this post is where, and on what, to sit in the garden! If you are reading this you are probably a gardener – during the growing season you do plenty of lifting and bending, squatting and kneeling. It’s okay to sit then – indeed you deserve to sit after long hours working in the hot sun.

So where’s the sweet spot for your sit spot? That depends on what you’ll be doing while you sit. Will you be eating dinner? Enjoying wine and canapés with a few friends? Or are you still working – sharpening your shears, mixing fertilizer or shelling peas? Or maybe you just want a place from which to admire your handiwork.

A few years ago I was conducting a pre-design interview with a new client. This fellow had been gardening for many years and wanted a couple of his own ideas incorporated into the design. I didn’t have a problem with this, but I did question one of his ideas. “I want to put a bench right there. Wouldn’t that look great?” he enthused, pointing to a spot a few meters away. “Hmmmm,” I answered noncommittally. All I could see was what he would be looking at from said bench – the large barren wall of his large home. I brought this to his attention. “I never thought of that,” he replied. We scrapped the bench idea and chose instead to put a small water feature in its place. Remember fellow gardeners, a sitting area isn’t just a pretty picture; it’s a destination – a place you want to go to and actually sit. So where it is situated is important; unless it’s only a place of work, it should offer a pleasing view. Even then, you might as well enjoy yourself while you shell the peas and shake the dirt off the potatoes.

Most important though, is functionality. To quote the late Steve Jobs, “It’s not just what it looks like….design is how it works.” In other words, wherever you’re going to situate that sit spot in your garden, and whatever it looks like, make sure it works for you. Some things to consider….

- Is there a smelly compost or dog run nearby? If so, maybe don’t sit there.

- Is there noise from a road or playground that would intrude on your quiet space?

- If your sit spot is a work space, do you need a water faucet close by?

- A dining area for enjoying full meals requires a site large enough for a patio table and chairs (trying to cut steak and eat corn-on-the-cob while sitting on an Adirondack chair isn’t very practical).

- Do you want a place to have a siesta in the sun, or some shut-eye in the shade?

- How much privacy will you want?

- Think about the comfort of what you are sitting on – do you need cushions or some kind of back support?

Of course there are still aesthetic considerations. The style of your seating should fit with the design as a whole – both proportionately and thematically. Colours and materials should be chosen accordingly. And don’t feel you have to stop at one seating area – even smallish properties can often accommodate more than one sit spot. Perhaps an area to sit and dine, and another quiet spot to sit and read.

Need some inspiration? Have a look….

A weathered wooden patio set fits perfectly with the rough-hewn posts and beams of the pergola – and what a view! Kraze Legz Winery, Kaleden. Photo: Sue Gaviller

This client’s yard backs onto a natural area – the patio was thus situated to view both the garden and the aspen grove beyond the fence. Photo: Sue Gaviller

The warm brown colour of the furniture works well with the warm tan shades of the flagstone patio. Two dwarf reblooming Syringa ‘Sugar Plum Fairy’ flank the seating area providing heavenly aroma – twice a year! Photo Sue Gaviller

The shape and colour of this modern patio furniture is a good choice for the contemporary rectilinear design lines of the landscape. Photo: Pexels

For small spaces, bistro sets are a good alternative to full size patio furniture; appropriate for meals (for 2 people) or for coffee and cookies. This homeowner has created privacy and an attractive view in a front yard setting by enclosing it with plantings. Photo: Sue Gaviller

When I designed this small seating area for a client, I didn’t know I’d end up sitting there frequently with her – sipping mojitos, Moscow mules, or our favourite; vodka tonics. It’s a cool, shady spot to relax on a hot summer day, with a spectacular view of the now-mature gardens. Photo: Sue Gaviller

These clients wanted a large conversation set to entertain friends around a gas fire table – the space had to be designed to accommodate large chunky furniture while still allowing access to the hot tub (behind the screen). Photo: Sue Gaviller

A bench under a vine-covered pergola offers respite from the hot California sun. Chateau St. Jean winery, Sonoma County. Photo: Sue Gaviller

A cozy spot to sit, sheltered by 3 mature Cologreen junipers and surrounded by flowering shrubs and perennials. CNIB Gardens, Calgary. Photo: Sue Gaviller

A faded wooden bench surrounded by ferns and fuchsias, fits the rustic exterior of the building.

Photo: Sue Gaviller

A bench outside the tasting room at La Frenz winery in Penticton is a feast for the eyes – a view of the pretty scented gardens up close and a view of the hills beyond. Photo: Sue Gaviller

In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree – crabapple blossoms carpet the ground around two stone benches at Reader Rock Garden, Calgary. Photo: Sue Gaviller

A gravel pathway leads to a stone bench beneath a fruit tree. Bylands Nursery, West Kelowna.

Photo: Sue Gaviller

A sunny spot from which to view the beautiful gardens at Kendall Jackson winery. Photo: Sue Gaviller

An old wooden chair, probably an original fixture, provides a moment of rest in the deep shade at Reader Rock Gardens, Calgary. Photo: Sue Gaviller

Covered verandas are a great place to sit and watch the world go by. This homeowner has beautified the sight-line with effective positioning of the gardens, including the use of the boulevard.

Photo: Sue Gaviller

Keep in mind there are dimensional recommendations for specific spaces. For example, allow about 2½ linear feet per person for sitting space – this provides ample elbow room. Provide at least 3 feet of clearance around a patio table so guests can comfortably push their chairs out when dinner is over. Leave 1 – 1½ feet between chairs or couches and the coffee table. This makes for much easier navigation when you have a tray of drinks and appies – spilled drinks, bruised shins, or stubbed toes just ruin the party. And allow for a little room around the outside of a conversation set too – at least a foot, more if access around the furniture is needed.

Regardless of shape, 3 feet or more of clearance around the patio table means comfortable movement when sitting down to dinner, or getting up afterwards. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

Left: A large conversation set requires ample room to move in and around comfortably.

Right: A bistro set, though small, still needs enough room to be functional – 2½ feet for the table, 2½ feet for each chair space and at least a foot all the way around. Graphics: Sue Gaviller

My sister’s dog Java, as a puppy, and still now as an old dog, thinks chairs are exclusively for his benefit. Of course he doesn’t care a whit about function or aesthetics. Photo: Cathy Gaviller

Well folks hope y’all enjoyed today’s post – it is the first in more than a year, and what I hope is the first in a series on garden elements; fences and gates, pathways, and other elements that help to personalize our gardens.

Till then, Sue

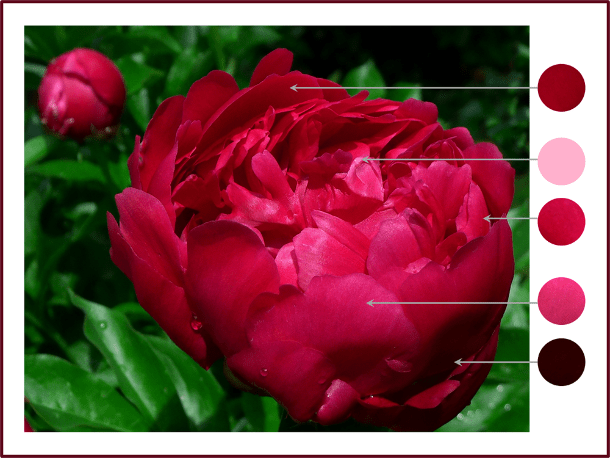

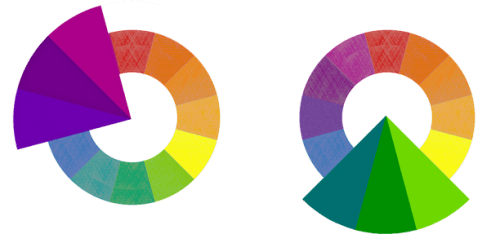

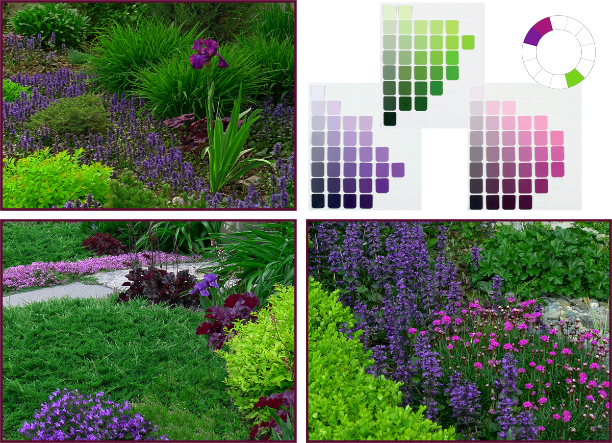

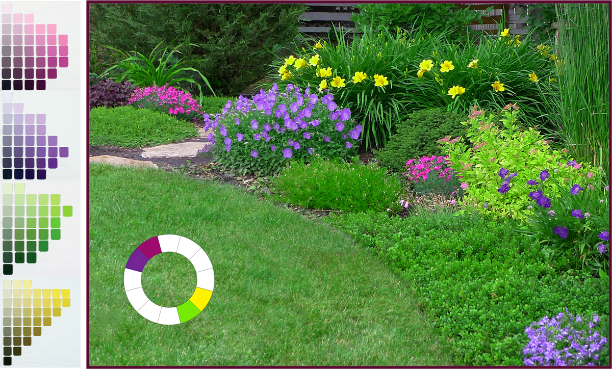

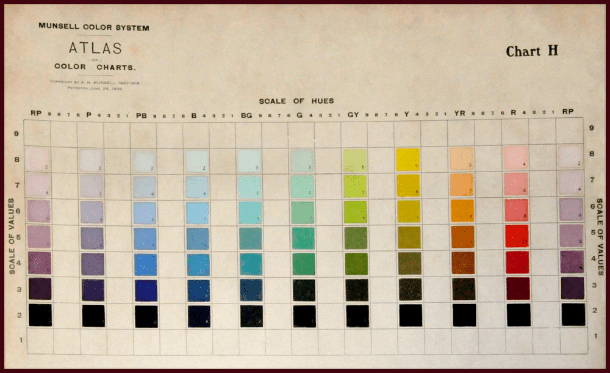

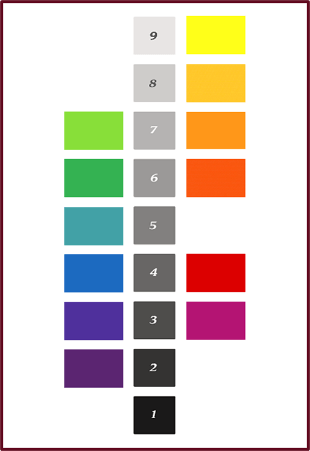

It’s important to note that the basic hues in their pure state don’t have equal values. If I were to pose the question, “Which of the spectral hues has the highest inherent or native value?” you wouldn’t have to think long before responding. You’d answer yellow right? It is obviously the lightest hue on the spectrum. Likewise you would probably intuit that the hue with the lowest natural value is violet or purple.

It’s important to note that the basic hues in their pure state don’t have equal values. If I were to pose the question, “Which of the spectral hues has the highest inherent or native value?” you wouldn’t have to think long before responding. You’d answer yellow right? It is obviously the lightest hue on the spectrum. Likewise you would probably intuit that the hue with the lowest natural value is violet or purple.